Josie and the Pussycats at 20: A pop-music oracle that didn't care too much about pop music

Take away Randy Newman's first Oscar and give it to "Three Small Words"!

The 1998 teen comedy Can’t Hardly Wait is, in many respects, a dumb and cartoonish take on the one-crazy-night-of-partying subgenre, a Dazed and Confused where all of the nostalgia is an accidental years-after-the-fact mutation of what was once craven popularity-courting. But it does have its moments, among them an inspired running gag about the high school band endeavoring to play the movie’s centerpiece blowout graduation party. When one musician dons the band’s own t-shirt against the lead singer’s wishes, he kicks off an intraband feud that derails the entire gig; the four friends have an acrimonious break-up and sentimental reunion, all before they’re able to play a note. As they’re about to celebrate their triumphant return, the cops raid the party and the whole thing gets shut down. Because this all takes place in the kind of accelerated teen-movie universe where characters are essentially expected to disappear after graduation, rather than linger around for a summer and see each other at subsequent college breaks, it’s easy to imagine that this is the definitive end of LoveBurger, the band in question. We’re left with no idea what they sound like, yet a perfectly workable idea of how good they probably aren’t.

To the extent that Can’t Hardly Wait has much of a take on pop music as a form, it’s pretty craven—part of the same preppie/poptimist fantasy that informs the rest of the film, dictating that Smash Mouth should be played no fewer than three times and Barry Manilow should become an inexplicable plot point, while the evocative Replacements tune that the movie takes as its title is halfheartedly shunted off to the end credits. (To be fair, this is realistic, in the sense that none of the characters in this movie would listen to the Replacements on their own time.) But in the gently mocking arc of LoveBurger, writer-director team of Harry Elfont and Deborah Kaplan do show an eye and an ear for the interpersonal side of making music and its accompanying images—the way that pop-music narratives make their way into our lives one way or another. And it’s that sensibility that they drew upon to make their next (and also last) film as directors: Josie and the Pussycats, an adaptation of the Archie Comics characters, which recently celebrated its twentieth anniversary.

Josie and the Pussycats was not a hit in 2001. In fact, Kaplan and Elfont inadvertently helped bookend the teen-movie boom of the late ’90s and very early ’00s: Can’t Hardly Wait laid the groundwork for a series of bigger hits like She’s All That and Cruel Intentions, and Josie and the Pussycats—starring the titular All That herself, Rachael Leigh Cook—provided proof positive (in form of moderate hype and anemic grosses) that these movies were no longer attracting their audience. By the end of 2001, Not Another Teen Movie became a gravestone for this era of teen comedy. The dominance of live-action Archie Comics characters would be deferred to the era of Riverdale.

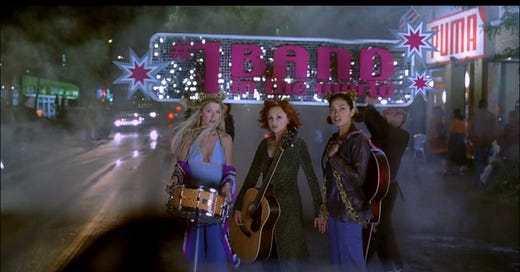

With twenty years of distance, though, it’s hard to even receive Josie as the teen comedy its marketing nominally described. The characters’ ages are nebulous; vaguely bohemian, vaguely collegiate, with some attitudinal hints of high school. (In any event, there are trend-chasing mean girls who know and mock the heroes.) No parents are visible or mentioned. I’ve seen the movie at least five times, and I wouldn’t swear to any of the three central characters taking so much as a sip of alcohol (though maybe they hold champagne glasses at some point), and the movie is tame enough that it was re-edited for a PG version on DVD, presumably in an attempt to recoup its costs by broadening its audience. The young-adult netherworld inhabited by Josie (Rachel Leigh Cook), Val (Rosario Dawson), and Melody (Tara Reid) makes perfect sense for the film’s real subject: using popular culture to sow the seeds of consumerism in young audiences flush with carefree spending money. That the Pussycats themselves split packages of ramen three ways is immaterial; they are an aspirational target market regardless of their actual economic status.

At the beginning of the film, other members of that target market are funneling their cash toward Du Jour, a parody of then-contemporary boy bands like Backstreet Boys and N’Sync—and played by two contentious members of LoveBurger (Breckin Meyer and Donald Faison) alongside two other Can’t Hardly Wait cast members. After serenading the audience with a music-video-like performance of their hit single “Backdoor Lover” (a double entendre every bit as subtle, delicate, and tasteful as the boy bands themselves), the movie shows them bickering on a private plane, echoing the pettiness of LoveBurger, before their manager Wyatt (Alan Cumming) gives a coded order (“take the Chevy to the levy”) and bails out, seemingly leaving the band to die in one of those iconic pop-music plane crashes.

Wyatt’s search for a pliable Du Jour replacement brings him to the Pussycats, apparently Riverdale’s only (or least-popular, anyway) pop-punk band. The movie eventually reveals that Wyatt and his unhinged boss Fiona (Parker Posey!) have selected the Pussycats, rechristened with Josie’s name out front, to serve as a conduit for their master plan: Rigging the marketplace with a hot new band, and embedding that band’s songs with subaural messages about which new products to feverishly covet—even which slang to use when describing those products. The slang of choice the movie lands on is “jerkin’”—as in “Josie and the Pussycats are the best band ever. They’re totally jerkin’!” It’s tastemaking as forced onanism. To further this messaging about messaging, the film Josie and the Pussycats is absolutely saturated with product placement—which, the filmmakers have said, was not actually product placement at all, at least in the sense of anyone being paid to use McDonald’s, Target, and other logos as set dressing. The more explicitly name-checked brands are perfectly 2001: Zima, Steve Madden, and mtv dot com.

All of this has been pointed out before; despite plenty of dismissive contemporaneous reviews, Josie and the Pussycats has since received its due for embedding a not-exactly-subliminal satire of consumer culture into a cute, cartoony comedy about a trio of likable gals experiencing the predictable pitfalls of sudden fame. What the movie doesn’t comment upon directly, but enhances its satire nonetheless, is how closely the Pussycats’ rise mirrors non-satirical movies about pop music, which make success in this world seem head-slappingly easy without the aid of nefarious corporate conspiracies. If Kaplan and Elfont are music geeks—and my guess is that they aren’t—they conceal it beneath a blithe treatment of pop music as a monolithic entity. No one in the movie mentions that Wyatt is attempting to replace a white-boy R&B act with a trio of girls playing rock music, and indeed, the very terms “rock” and “pop” are used interchangeably throughout. No one in the Pussycats shows any disdain for Du Jour, even if the movie mocks Du Jour fandom by making the meanest, most status-obsessed characters into boy-band acolytes. When the Pussycats have the opportunity to appear on the then-dominant MTV countdown program TRL, Josie offhands “I love that show!” without a hint of irony. It’s hard to tell whether the movie is reluctant to bite the hand that feeds it Carson Daly cameos, or simply making Josie, Val, and Melody too sweet-natured for music-industry, or even music-snob cynicism. (Well, in the case of Mel, it’s not hard to tell at all: Reid plays her as that most disturbing of creatures, a sexy Ralph Wiggum.)

In other words: Are Kaplan and Elfont poptimists, or satirizing the blossoming top-40-fits-all aesthetic of poptimism before it even took hold? That both cases can coexist in the same movie is a big part of why Josie and the Pussycats feels prescient even as it looks ever-more like an early-2000s time capsule. Cinematographer Matthew Libatique, then best-known for his work with Darren Aronofsky and now perhaps the most diversified DP in the comics-to-film industry (having shot Josie, the first two Iron Man pictures, Venom, and Birds of Prey) captures the intense, blown-out color schemes of a music video by McG or Marcos Siega, which is the look so many of those late-’90s teen movies seemed to be aiming for, and the juxtaposition of boy bands and sugary pop-punk is exactly depicted in Siega’s 2000 music video for Blink-182’s “All the Small Things.” Whenever the movie needs the Pussycats to show unforced friendship and bonding, it’s delivered in music-video-style montages. The opening-credits sequence introducing their humble lifestyle as a scrappy local rock band is not so different in tone from the ascent-to-stardom sequence scored to “Pretend to Be Nice,” which blurs the line between the music video they’re making and the music video they’re living.

This may be why the movie never makes a hard contrast between the scrappy realness of the Pussycats versus the overproduced posturing of Du Jour. Of course, in reality both bands are equally prefab. Josie’s vocals are not provided by Cook; her voice is played by Kay Hanley from Letters to Cleo (also seen up on that roof at the end of Ten Things I Hate About You), and the songs were written by an all-star team of musicians and producers, including Fountains of Wayne’s late, great Adam Schlesinger (“Pretend to Be Nice”), Adam Duritz from Counting Crows (“Spin Around”), and album producer Babyface, alongside Elfont and Kaplan. They’re the kind of impeccably movie-made tunes whose absence from the Oscars damages the Academy’s reputation more with every passing year; revoke Randy Newman’s first Oscar and give it to “Three Small Words,” I demand it! Even without the film world’s highest honor, the soundtrack album went gold—not a huge number at a time when CDs were near-peak and hit albums could move a million copies a week, yet enough to represent a bigger commercial success than the movie it accompanied.

Maybe that’s because the soundtrack packaged the movie’s pop-forward, genre-agnostic sensibility for an industry that was already starting to embrace it. The crucial addition to the movie version, of course, is the story that explicitly calls out pop music as the tool of older, insecure, profit-driven, power-hungry lunatics. The cheerful zaniness of the era-appropriate trend-chasing depicted here (one outfit is described in the content labs as “Buffy meets Chicken Run”) offers a flipside to poptimism that would sometimes be forgotten as the decades wore on and music critics were increasingly expected not just to tolerate the most popular acts on the charts, but advocate for them as unfairly maligned. (And though there are certainly one-off records that received a bum rap from the entrenched sexism of music journalism—hello, Liz Phair’s self-titled pivot towards pop!—it’s difficult to think of many super-popular musical artists who have been consistently and unfairly maligned in my adult life. Eminem was treated as one of our most important artists for years.) Yes, it’s true that rock trios are not inherently more authentic or valuable than pure pop acts; Josie and the Pussycats adds that this truth doesn’t clear out the consumerist messages embedded into prefab pop (or any other music). I have no idea if Elfont and Kaplan were inspired by the Abercrombie shout-out in the 1999 LFO song “Summer Girls,” but their movie takes that sensibility to a hilariously logical extreme.

If the movie obliterates any sense of old-school rock-and-roll authenticity in the process (and, from a music snob’s point of view, holds a pretty limited view of rock and roll in general), it at least does so gleefully, with a studio filmmaker’s knowledge of the entertainment industrial complex. An obnoxiously oft-repeated defense of boy bands back in the early 2000s was that the Beatles were considered boy bands of their day. Josie doesn’t address this comparison directly, but it at least frames the boy-band/rock-band contrast in a way that’s irreverent toward the whole corporate-music charade, rather than conferring some imagined artist integrity upon Lou Pearlman’s boys. Despite Wyatt falling short of Lou Pearlman levels, again the movie proves prescient, anticipating more sympathetic view of boy bands as performers manipulated by promises of fame and fortune, one that would later become more commonplace in the culture. Du Jour are still a bunch of squabbling, image-obsessed bozos—LoveBurger gone global, essentially, with Seth Green bringing in some poseur moves from his culturally appropriating Can’t Hardly Wait characters. They’re also good-hearted, harmless-at-worst guys at the end.

Speaking of the end, wherein Du Jour returns, not dead, to help expose Wyatt and Fiona and validate the Pussycats’ resistance of their consumerist agenda, and the Pussycats play the biggest gig of their lives to an audience that will no longer be brainwashed into automatically liking them: Elfont and Kaplan don’t seem to know exactly how to resolve this contradiction between satire and poptimism. The movie kinda throws up its hands, and goes back to high school for a gaggy reveal: The slick, fashionable Wyatt and Fiona are actually just former teenage outcasts (unwittingly from the same high school, no less) who want desperately to decide what’s cool and fashionable. Granted, this revelation is seeded earlier in the film, when Josie questions the way that former enemies are now begging her for attention, and Wyatt asks her, “what’s the point of being famous if the people who you hated in high school don’t wanna kiss your ass?” Posey’s performance seizes even more fervently on the idea of Fiona as reinvented weirdo: During a party she throws for her new project, she performs a deranged pantomime of girl-talk bonding, agonizing over a single potato chip and bouncing on a pink-dressed bed. It’s one of her best major-studio acts of scene theft. Even so, the conception of corporate chicanery as an arrested teenage popularity contest feels a little trite. Are the rest of the record execs the good kind of preppies, the ones who were too well-adjusted to disguise their high school traumas? As in Can’t Hardly Wait, Elfont and Kaplan don’t show much kinship for the nerds of the piece; more affectionate amusement at their cluelessness.

Their hearts are ultimately with the Pussycats, who don’t have much character one way or the other, beyond looking pretty and acting nice. Most of the conflict is caused by Josie innocently succumbing to the messages buried in her own songs. She listens to a new remix, and gets delusions of grandeur—a potent metaphor that nonetheless fails to draw any genuine bitterness out of Cook’s unassuming sweetness. The Pussycats play new songs at their big concert, and the audience likes them anyway, without the aid of subaural monkey business. Not much of an ending; also not a huge departure from where music fandom eventually went following the early-21st-century pop explosion.

Now, of course, the messages aren’t subural, or even necessarily corporate. They come straight from stars’ social media accounts, and if there aren’t secret codes instructing fans to attack anyone who’s getting on the artist’s nerves, plenty of Taylor Swift fans will find those message anyway, and react with the same single-minded zeal as the “pink is the new orange” crowd in Josie and the Pussycats. Music stars may do endorsements x partnerships, but the real corporation they serve is themselves. (Just look at Riverdale, where the Josie character, still a singer, is surrounded by three or four other cast members who clearly fancy themselves multi-hyphenate pop stars in the making.) It’s the final step that the movie, bouncy and confectionary as it intends to be, fails to visualize; when its music stars speak their minds, they don’t say much to bother anyone and everyone seems to have a nice time. Yet even at Josie’s most (p)optimistic and ridiculous, it’s more observant about the music industry than, say, the insultingly moony-eyed likes of Begin Again, with Mark Ruffalo angrily insisting that new discovery Keira Knightley must release her album for free with no promotion, a strategy that would make sense mainly if she was playing the character of Radiohead. (She is not.) Or think of The High Note, where Tracee Ellis Ross plays an aging global superstar whose label nonsensically gives her an ultimatum, demanding she choose between a Vegas residency and a new album. These movies take pains to explore a changing industry, and sound as phony as ever. Josie and the Pussycats pointedly doesn’t much differentiate between squabbling teenagers and driven artists; it only barely considers the idea that the latter might exist. It’s both celebratory of pop music and emotionally detached from it. The made-up slang has it: The movie is totally jerkin’.